working on a piece about owls … to come.

personal images from the space: rock types, pencil shavings, and sketchbook-journal for scratching away at ideas. And lukewarm tea, which I forgot to drink after falling into the flow.

working on a piece about owls … to come.

personal images from the space: rock types, pencil shavings, and sketchbook-journal for scratching away at ideas. And lukewarm tea, which I forgot to drink after falling into the flow.

The forest trail had survived worse. Mountain forest snowstorms are often the last vestiges of snow and ice, clinging until deep July. Frozen land. Thawed land. Animal bones litter these parts. Years of shoes, mountain bike tires, paws, and hooves wear their curves into the land's memory.

A few days after the winter inversion lifted, I went for a trail run with the dogs. The familiar firmness of winter dirt was not there. Instead, the ground gave way—straight down, no warning, no slide. Just a sharp crunch, and my feet kept dropping into the ground, like a spoon cracking the top of creme Brule. It was as if the earth had exhaled each time my feet hit the trail.

I adjusted, slowed, and paid attention. The earth could not hold me: crunch, pop, hollow sounds. The ground was lying.

What unsettled me wasn't the sensation itself but how quickly my body lost trust. Muscles tightened. Balance recalibrated. I began walking the way you do on unfamiliar ice, even though there was no ice to see. The ground had changed its rules without telling me, and my body knew it before my mind could catch up.

The rocks on the trail finally stopped me. They had fallen straight down into the trail, leaving behind precise outlines of their negative space. Not scattered, not rolled away—just dropped, straight down. The earth held them, then let them go, just as all lives lived.

Our typical knowledge is

ground = compresses;

ice = shatters.

This was

ground = shatters.

Photos from my personal archive of the Cascade Range: (left) long shot of wintry mountain range; close-up of thawing ground; frozen fog on forest road; night skiing lights on mountain ridgeline.

Ice formed in the dark. Water migrated upward. Structure rearranged itself while I went on with my days, unaware. Ice had formed not on the surface but inside the soil itself; thin sheets stacked as a quiet architecture (i.e., ice lenses). When the sun returned, it softened only the top layer, leaving a crust-over emptiness. Welcome to a freeze-thaw segregation of soil physics.

My point load was ruining the trail; normally, it's spring, when the land managers advise staying off the trails to prevent destroying surface uniformity. But here I totally ruined it in winter.

I kept thinking about how I trusted the ground when I wasn't next to a slope. How much of my life do I move through it that way, assuming support is inherent rather than conditional? Assuming what holds me up today will hold me tomorrow simply because it always has.

We often think of collapse as something dramatic. Loud. Sudden. But this wasn't that. This was quite weak. A slow exchange of one state for another. A surface that continued to look like itself long after it had lost the ability to bear weight.

The trail will recover. The soil will settle. The ice will disappear completely. From the surface, nothing will mark where the ground once gave up. It won’t remember me, but it will stay with me.

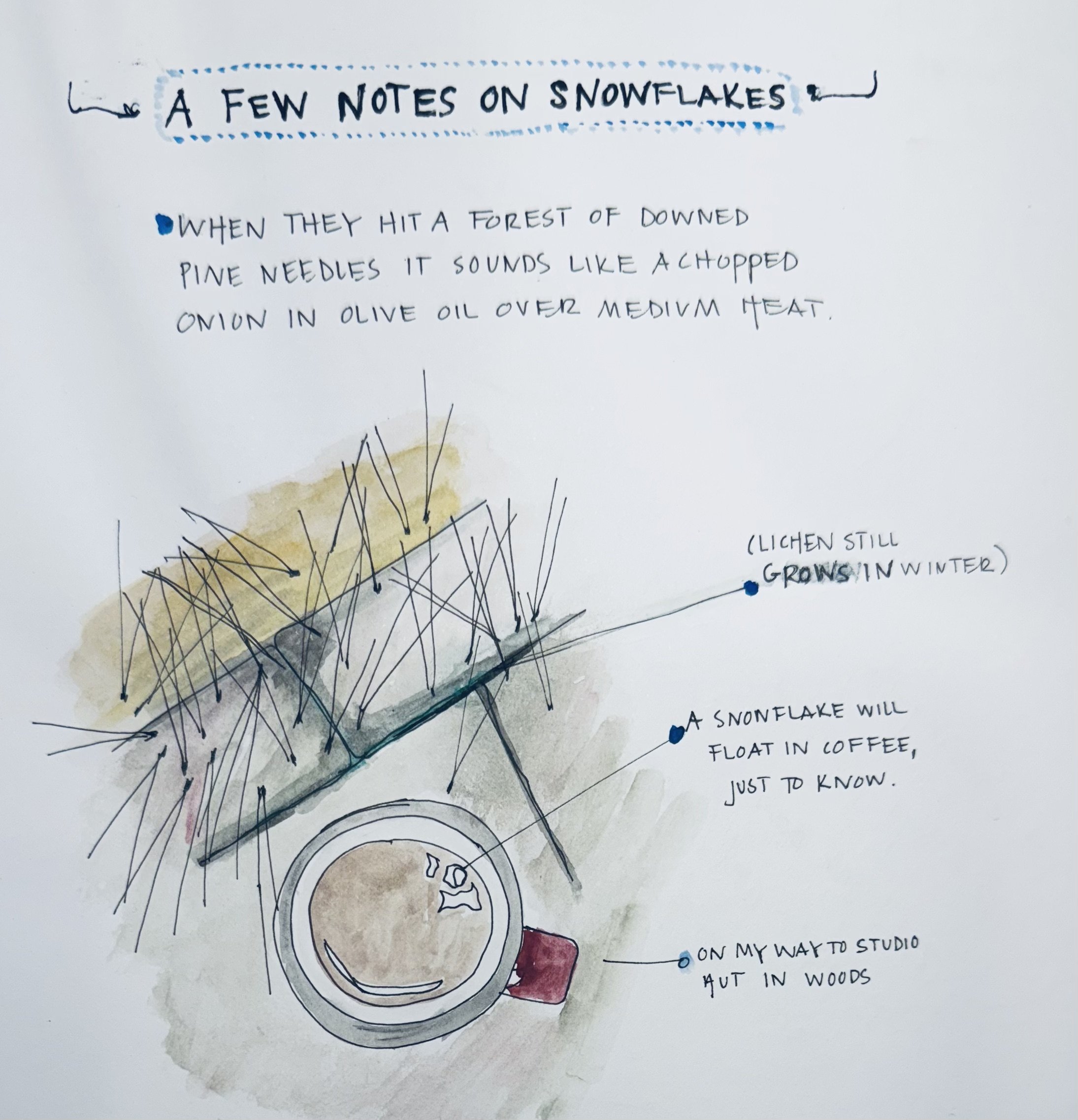

For a week and a half now, frozen fog pressed down, laying rime ice. Every twig, wire, and conifer needle was rimmed in frosty lace. The stillness hummed.

This winter, so far, has kept itself quiet. Nights run long and clear. Cold air doesn’t rise — it drapes low, sliding downslope and settling into the valleys, folding itself in. The fog doesn’t lift. It stays. And stays.

Each morning, the world reappears softer. The same forest, the same ridgeline— only now they wear a memory of moisture. Rime ice builds in slow increments, feathered and fine, like time itself is catching on edges.

This is what an inversion does: holds the world in pause, asks you to notice how silence accumulates.

““...The life you lead is your art and the art you make is your life.””

I fondly remember studying Mann’s early work as a budding darkroom photographer who traveled great distances to see Photography ART wherever I landed or lived.

Now she’s 74, passing on her wisdom in Art Work. Life is short, and I’m listening and doing what needs to come next. What will survive, what will linger, what will whisper from time to time among one mind or many?

Down a forest road, walking, looking for the year’s tree. PNW

“...to stand on the meeting of two eternities, the past and future, which is precisely the present moment...”

Hiking in the PNW | 2025

“Outside, shadows trade places with a sliver of sun, which trades places with shadow.”

-Gretel Ehrlich | Islands, The Universe, Home

Shots from backcountry camping and travels | PNW | 2025

“Like air, water physically links us to Earth and to all other forms of life.” - The Sacred Balance, David Suzuki

(1). Wildfire pollution. Wildfire sunset. August 2025

(2) Wildfire pollution. Wildfire sunset. August 2025

Astronomy Ampitheater | Nevada

Have you ever met someone so confident and grounded that they don’t talk about themselves? They don’t need to. Either you know who they are, or you don’t—and either way, they couldn’t care less. The sky over Great Basin National Park is like that. It doesn’t need to impress you. It just is. And when the horizon slices out the Snake Range like a quiet blade, you feel the gravity of that presence.

Earth exhales here in basin and range. And the sky? It becomes a slow-moving theater where twilight performs in three deliberate acts—civil, nautical, and astronomical. Each phase unfolds, deepens in hue, then dissolves into the next.

The elevation starts at 6,000 feet and climbs to 13,000 feet if you summit Wheeler Peak. The air is dry, crisp, unbothered. You won’t find crowds—just a couple of roads leading to nowhere in particular. The nearest town, Baker, claims a population of 23. Someone sells ice from their porch if you need it. And instead of a little free library, there’s a take-a-stick-leave-a-stick setup for dogs.

If you come here, come ready—food, water, gear. Self-sufficiency is the unspoken language of the place.

Great Basin is a certified International Dark Sky Park. At night, the Milky Way doesn’t simply appear—it commands. You’ll stare up so long your neck will ache, locked in celestial conversation. The birds disappear. The stars stay.

Welcome, summer. This is what it’s like to hang out with astronomers.

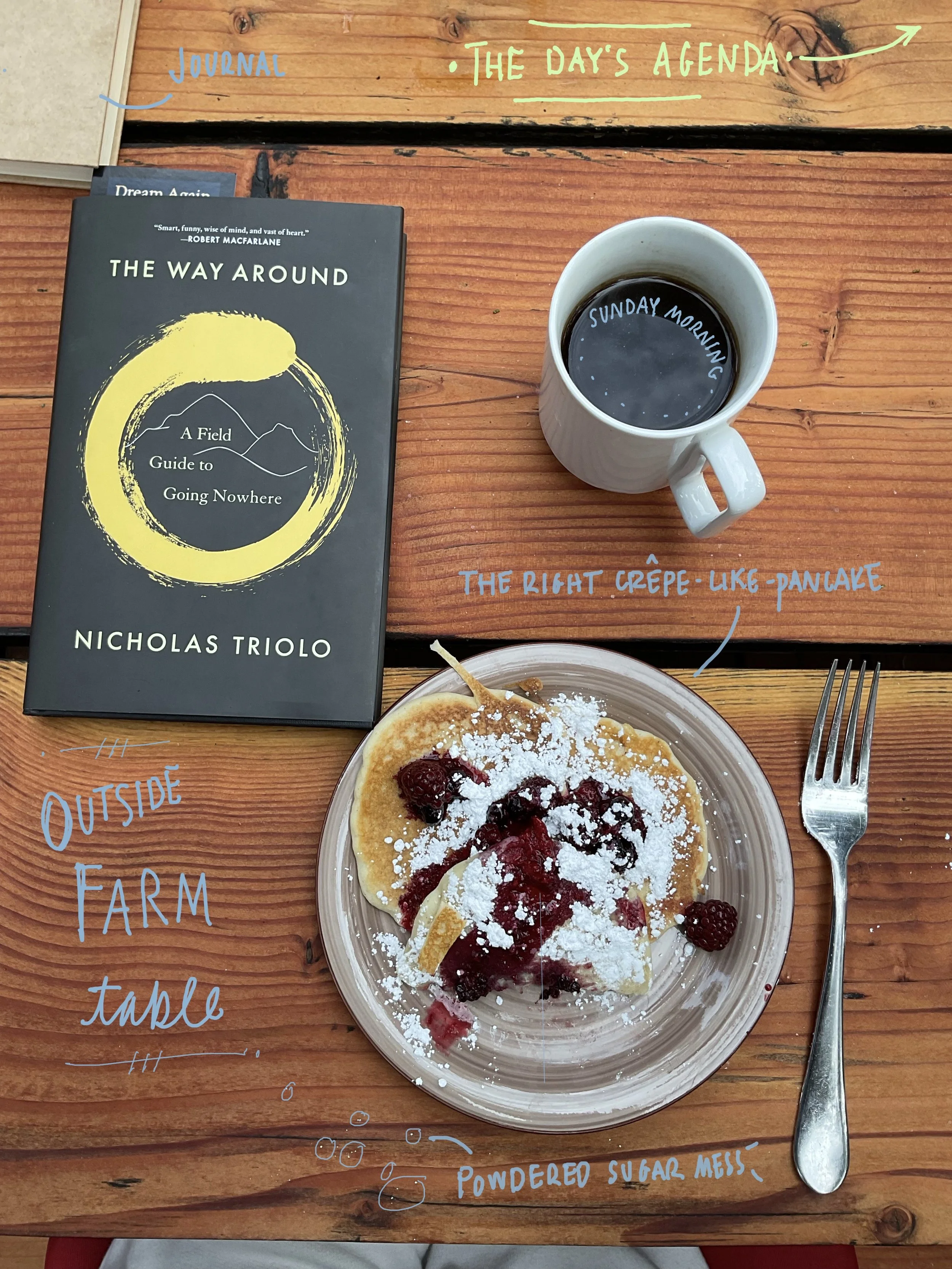

We started in the front section of an indie bookstore, then wandered separately but circled the genres.

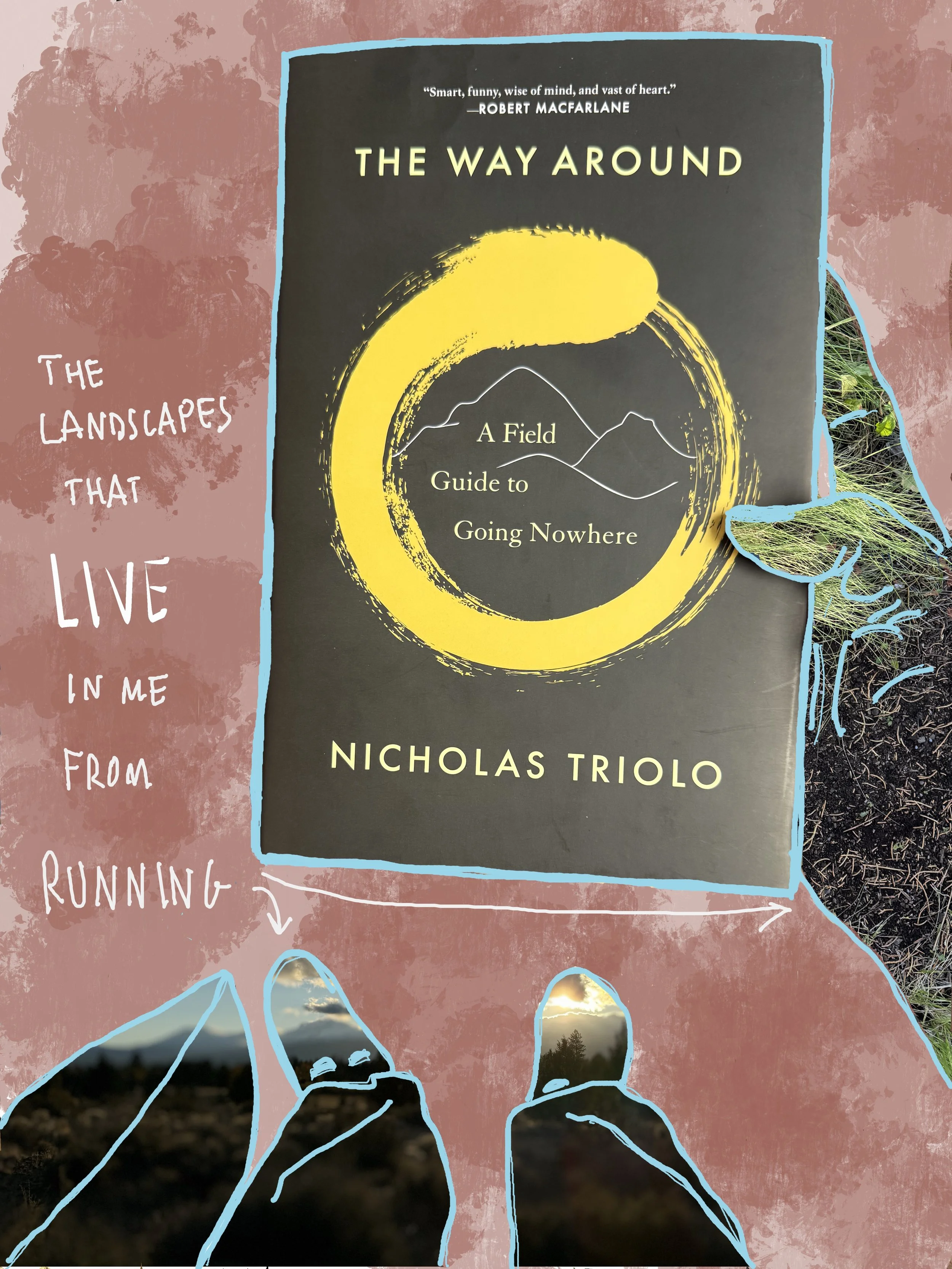

He found me and handed over a book. “This one’s for you,” he said. “It’s very you.” Nicholas Triolo - the shapes of his name matched the Enso Zen Circle.

By the end of our bookstore crawl date, we’d gathered eight books between us. He carried them in a brand-new fabric tote, which also held my fresh pair of jeans—and later, a half-eaten, shared bag of sea salt & vinegar avocado oil chips from lunch.

Back home, I made tea. We sorted our finds:

• His stack: military history.

• Mine: writing, photography, nature.

I cracked open “The Way Around” and paused at the prologue: “What are we encircling? What is encircling us?”

Out the window, the forest answered in stillness.

The weekend’s gaze held a little longer—read a book, limb some trees.

“We must learn to treat the earth as our home, not with authoritarian domination but by responsive cooperation.”

”Reclaiming the American Landscape”

The Aesthetics of Environment

Arnold Berleant

Photo from a recent morning when my lungs were filled with mountain air. The little Quaking Aspen leaf had nowhere to go but to be in the sunrise. At that moment, me too.

In the early 2000s, I attended a lecture by Robert Sobieszek, the Director of Photography at LACMA, about the “Ansel Adams at 100" exhibit he curated. I remember he said that adding “-scape” to a word—like landscape or moonscape—is a human invention. It stuck with me.

A mountain range isn’t a landscape until we frame it as one. The “-scape” signals more than just what’s there; it marks how we choose to see it. We’re not just observing—we’re interpreting, shaping, and naming what we see. That small suffix reminds me how much of the world becomes visible only when we decide to see it a certain way. Framing each moment sets up our mindset, our vision, and our actions.

Moonscape, near midnight, Humboldt County, Nevada | backcountry camping | 2025

Photo of my field notebook in the left corner; right corner faded with a ray of orange sunlight against navy pants. Exploring remote Nevada. 2025

Mormon cricket migration…umm...

Driving across northeastern Nevada, we crested a rise and slowed. The pavement was peppered with a reddish something. Was it leaf litter or cinder scattered across the road? Some of the reddish-withering bodies moved, while others did not. Thousands of Mormon crickets swarmed across the asphalt like some post-apocalyptic trail crew for about 100 miles.

So, what causes this biblical-style migration?

Turns out, it’s not just wanderlust. It’s hunger and fear.

Mormon crickets (Anabrus simplex) are actually flightless katydids, native to the western United States. Every few years, their populations boom, and they start moving in bands that stretch for miles and can travel up to two kilometers a day.

Here’s the weird kicker: they’re cannibals. If a cricket slows down, the one behind might bite its abdomen or legs for a protein-rich snack. This constant threat of being eaten keeps them moving forward in a tight formation. One study described it as a forced march driven by protein and salt deficiency, with cannibalism as both carrot and stick.

If the landscape is drying out and protein is scarce, they march. If another cricket’s back looks juicier than the cheatgrass around them, they bite.

Two open-access studies to explore:

Bazazi S, Ioannou CC, Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Torney CJ, Lorch PD, Couzin ID. The social context of cannibalism in migratory bands of the Mormon cricket. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 14;5(12):e15118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015118. PMID: 21179402; PMCID: PMC3001859.

Simpson, et al. Cannibal crickets on a forced march for protein and salt, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103 (11) 4152-4156, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508915103 (2006).

The answer’s not mystical: blacktop gets warm, holds heat, and stretches uninterrupted across the barren landscape. They follow the cricket ahead of them. The result is a pulsing movement that blankets (in depth!) along the highway for miles.

When vegetation dries out and predators are scarce (following wildfire, drought, or overgrazing), these migrations become even more intense. It’s ecological choreography, tuned to drought cycles, heat, and opportunity.

Mormon crickets might seem like a curiosity, but they impact everything from rangeland health to road safety. Ranchers watch them strip fields bare. Highway crews struggle to keep roads passable. Hikers (and explorers), like me, watch—horrified and fascinated.

In a world obsessed and glued to scrolling social media, this living river of insects is a reminder that nature still moves on its own terms.

The “tropical habitat” deep in my brain is to run far (in the forest and mountain trails, preferably). Humans are made to run. Scientists call it the “endurance pursuit (EP) hypothesis”. (See the Eugene Morin (anthropologist) and Bruce Winterhalder (anthropologist and ecologist) Nature Human Behavior article from May 2024.)

For the past decade, when given time away from work, I have consistently opted for outdoor activities (i.e., running, hiking, camping, backpacking, skiing, dog walking, roaming, etc.), regardless of the weather. (Essentially, REI loves me.) Such time well spent has also diminished my output for all things creative, original, and publishable. So, I’ve made a pact with myself to start a Creative Energy Map that summarizes and categorizes all of my starts, stops, and pivots from the last decade or so of content stored in my journals, field notebooks, and brain.

I consistently encounter the writerly advice: if you know what you’re going to write about, don’t do it; only write about what you don’t know is coming. So, that’s the plan: no plan on knowing what I’m going to write about. This ushers in organic flow and hot impulses to follow.

Let’s see where all of my sporadic randomness goes into a larger work. And as humans, we also look for patterns. So, here’s to pattern-looking, then, the OG AI - the human brain.

Personal achievement and bragworthy (obviously): I turned a non-bird person into a birding person. Now he sends photos of new species. Look up! Listen! There’s a whole world going on above your head that’s not on your phone. He said, “I never really knew until now.”

“The past always comes clearer, in the future.”

Overstory. by Richard Powers

Corvallis, Oregon | 2025

When you hit dense fog-lightning storm-hail-sleet-snow in the span of a half hour and it stays: Welcome to camping in Wyoming at elevation. One dog whined and whimpered from the crack and booms.

Menagerie Wilderness in the morning.

Bookstore in the afternoon.

Camping in the evening.

A winter road in the PNW.

I run, no matter the weather. Snow crunches beneath me, and my breath rises in steady clouds that hover in my face. The cold doesn’t deter me; it sharpens. Each mile carves space in my mind, like footprints marking the path forward.

The afternoon arrives slowly, settling like snowfall or deep rain. A hot cup of tea in hand, I watch the world outside shift from day to dusk. Sunday, in all its simple rituals, feels like enough.

New snow. Blue hour. Vibrant feelings.

All copyright Tricia Louvar. No reproduction of contents without written consent from Tricia Louvar.