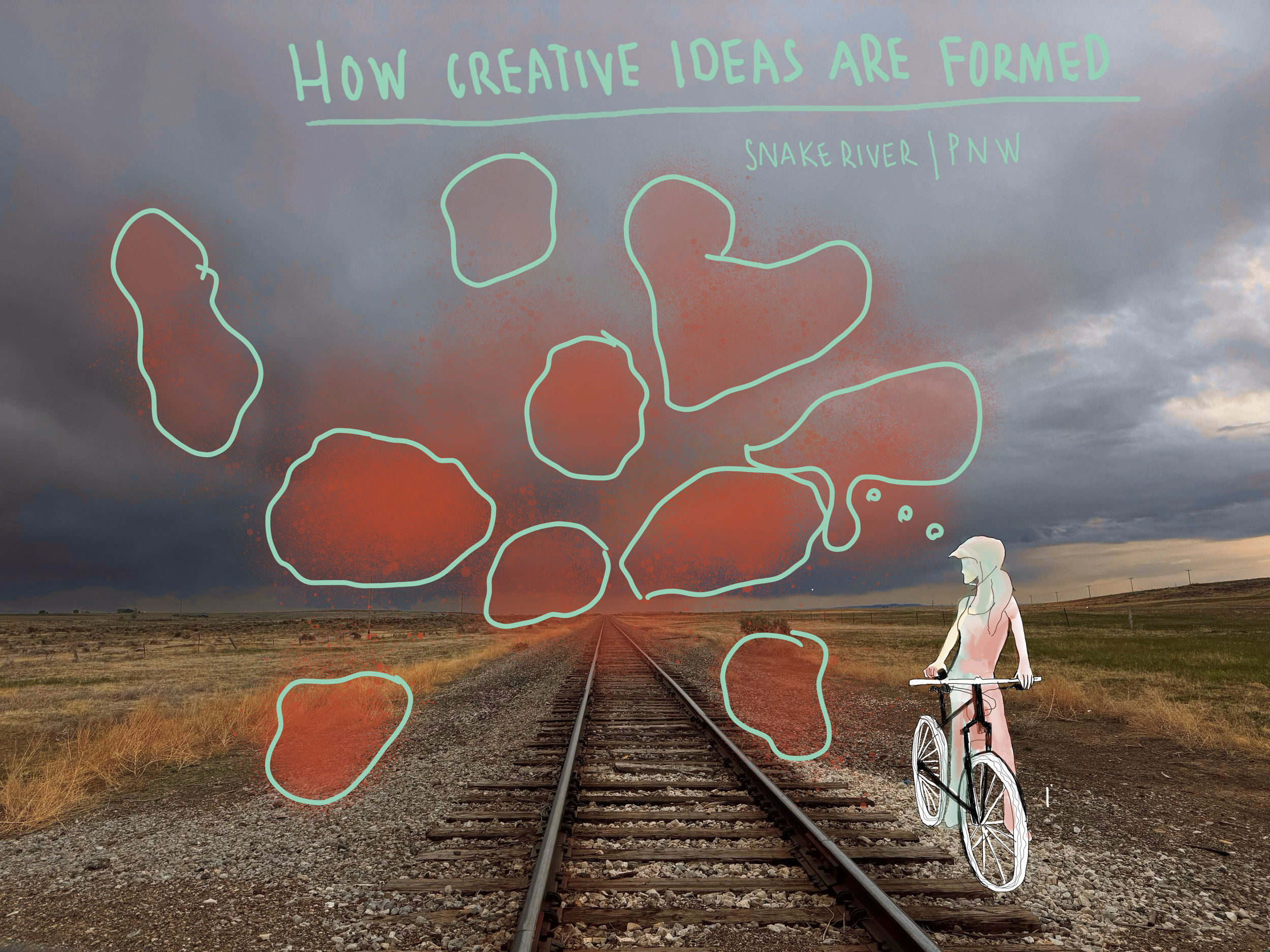

Mormon Crickets in Motion

Driving across northeastern Nevada, we crested a rise and slowed. The pavement was peppered with a reddish something. Was it leaf litter or cinder scattered across the road? Some of the reddish-withering bodies moved, while others did not. Thousands of Mormon crickets swarmed across the asphalt like some post-apocalyptic trail crew for about 100 miles.

So, what causes this biblical-style migration?

Turns out, it’s not just wanderlust. It’s hunger and fear.

The Science Behind the Swarm

Mormon crickets (Anabrus simplex) are actually flightless katydids, native to the western United States. Every few years, their populations boom, and they start moving in bands that stretch for miles and can travel up to two kilometers a day.

Here’s the weird kicker: they’re cannibals. If a cricket slows down, the one behind might bite its abdomen or legs for a protein-rich snack. This constant threat of being eaten keeps them moving forward in a tight formation. One study described it as a forced march driven by protein and salt deficiency, with cannibalism as both carrot and stick.

If the landscape is drying out and protein is scarce, they march. If another cricket’s back looks juicier than the cheatgrass around them, they bite.

Two open-access studies to explore:

Bazazi S, Ioannou CC, Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Torney CJ, Lorch PD, Couzin ID. The social context of cannibalism in migratory bands of the Mormon cricket. PLoS One. 2010 Dec 14;5(12):e15118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015118. PMID: 21179402; PMCID: PMC3001859.

Simpson, et al. Cannibal crickets on a forced march for protein and salt, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103 (11) 4152-4156, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508915103 (2006).

Why the Road?

The answer’s not mystical: blacktop gets warm, holds heat, and stretches uninterrupted across the barren landscape. They follow the cricket ahead of them. The result is a pulsing movement that blankets (in depth!) along the highway for miles.

When vegetation dries out and predators are scarce (following wildfire, drought, or overgrazing), these migrations become even more intense. It’s ecological choreography, tuned to drought cycles, heat, and opportunity.

Why It Matters

Mormon crickets might seem like a curiosity, but they impact everything from rangeland health to road safety. Ranchers watch them strip fields bare. Highway crews struggle to keep roads passable. Hikers (and explorers), like me, watch—horrified and fascinated.

In a world obsessed and glued to scrolling social media, this living river of insects is a reminder that nature still moves on its own terms.